It’s easy to love Sonic Mania. PagodaWest and Headcannon’s take on Sega’s emblematic hedgehog delighted skeptical critics and satiated ravenous fans. The odds of this happening—of Sonic narrowly escaping his cursed cycle—were not tough to bet against. Despite a smattering of dissimilar attempts across a variety of platforms, there wasn’t a Sonic game that nailed it like his 16-bit heyday. Sonic Mania, on the other hand, accepted Sonic’s inherited limitations (or problems) and transformed them into practical solutions.

Problem #1 2D or not 2D

Problem #1 2D or not 2D

Pulling Sonic out of 3D hell and away from nostalgic modernity risked alienation from the young and cries of blasphemy from the old. “New” Sonic fans (which are impossible to define, but we’ll just say “came to Sonic after Sonic Adventure“) first knew Sonic in a three-dimensional world. The lack of acceptable control, the poor lock-on mechanic, the proliferation of insufferable, pathetic characters — these are not perceived as negatives. They’re defining parts of Sonic, much the same way the entirety of Scrap Brain Zone, Sonic Spinball’s agonizing music, and Sonic CD’s haphazard level configuration are part of Old Sonic. Flaws are easier to overlook if they’re part of a game you fell in love with.

In the past, Sega met Sonic’s demand for a 2D plane with a compromise in 3D space. Sonic the Hedgehog 4’s two episodes embraced the popular 2.5D aesthetic but suffered under a regrettable physics system and a cynical delivery method. Around the same time, Sonic Generations pulled Sonic closer to home, but only for half the game. These two approaches made sense in 2011 and 2012. It’s where 2D gaming felt comfortable and Sonic seemed like a good retro-fit, but it didn’t feel like Old Sonic. For whatever reason, Sega wasn’t comfortable with a true pixel reconstruction of Sonic’s 16-bit aesthetic.

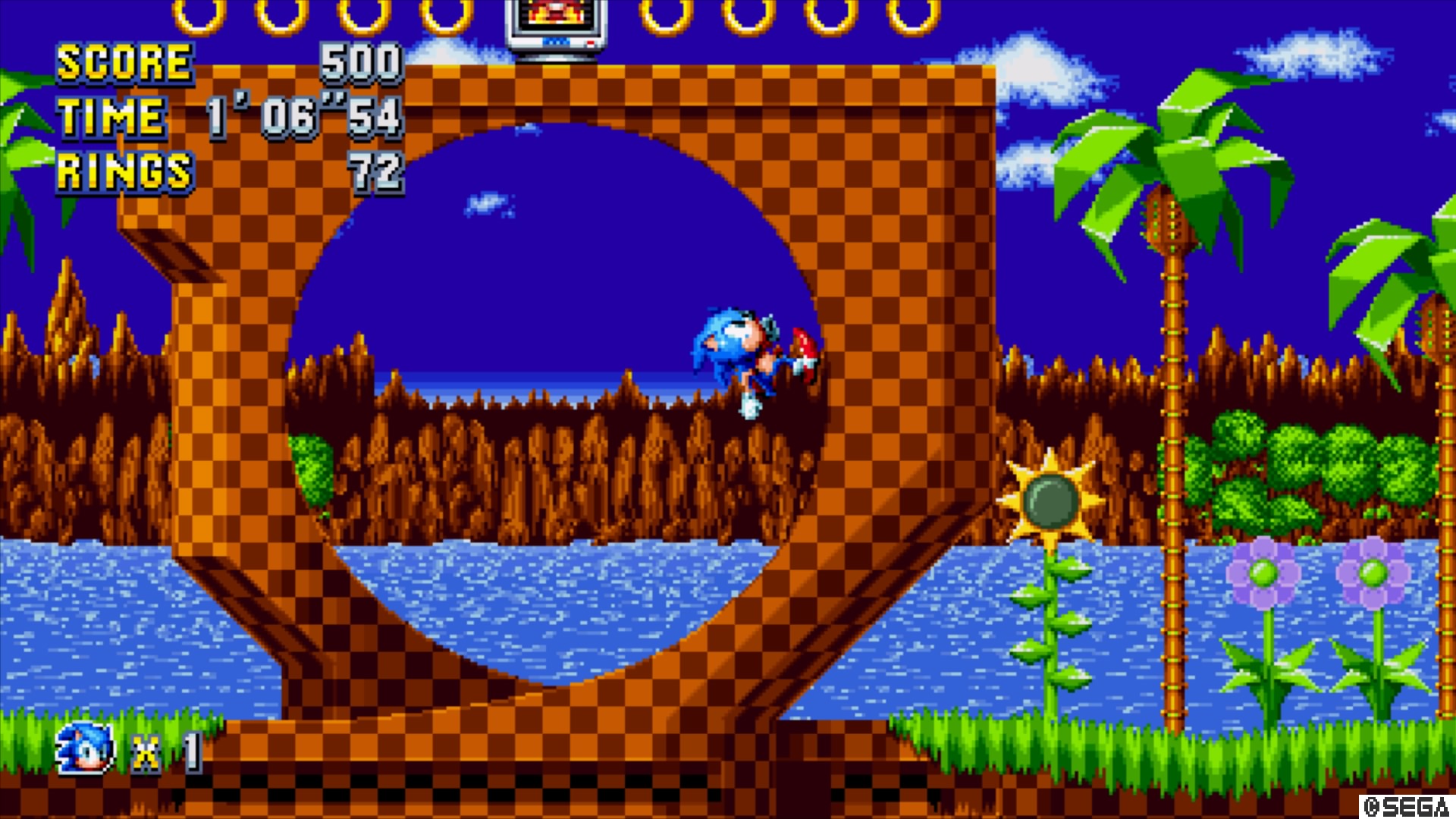

Solutions that were not obvious in 2011 make more sense today; just literally make a game that looks like Old Sonic. Gorgeous pixel art, emotive sprites, engaging level gimmicks, and sprawling pathways were defined by Sonic the Hedgehog and perfected around Sonic the Hedgehog 3 and Sonic & Knuckles. Sonic Mania’s characters are better animated, its color pallet and level size extends past the Genesis’ limitations, and there’s zero slowdown, but it all feels like it could be a 16-bit game. The idiom, “it’s what you remember Sonic playing like instead of what Sonic actually played like,” may be trite and overused, but it’s also valid. In a world where the PlayStation didn’t exist and the Saturn was allowed to be a 2D power house, Sonic Mania’s style may have mirrored Sonic’s first Saturn entry.

Problem #2 Sonic Team

Problem #2 Sonic Team

The machinations that drive Sonic Team are, as a measure of pure speculation, chaotic and grueling. Over the last ten years, Sonic Team had a hand in over a dozen Sonic games (along with sequels to both Nights: Into Dreams and Phantasy Star Online). With the exception of Sonic and The Secret Rings and Sonic and the Black Knight, both auto-running Wii experiments, none were direct sequels. Sonic Unleashed, Sonic Colors, Sonic Lost World, and Sonic Generations are all wildly different Sonic games – and each could have seen improvement from a proper, industry-standard follow-up.

There is virtue to be found in not settling on a single idea and constantly moving forward, but there’s usually also a creative (and financial) incentive to taking another crack at a foundational premise. Look at the relationship between Assassin’s Creed and Assassin’s Creed 2, Mass Effect and Mass Effect 2, and Uncharted: Drake’s Fortune to Uncharted 2: Among Thieves. Each make the original feel like a prototype, a mess of ideas too valuable to throw away and too potent to leave unrefined. Sonic Lost World, in particular, was a genre-spinning concept left to twist in the wind. It should have been better and it never got a second chance.

In fairness, Sonic Team has slowed their recent output. Development of Sonic Boom was handed off to Big Red Button and Sanzaru for its Wii U and 3DS entries, respectively, leaving Sonic Team without an AAA project on the market since 2013. Sonic Forces will change that this November, obviously, but it speaks to their magnetism toward larger products. It’s been over twenty years since Sonic & Knuckles, and much of the staff from Sega Technical Institute and Sonic Team, other than Takashi Iizuka, are no longer present at Sega. A 16-bit styled Sonic game could never come out of present day Sonic Team.

Enter the Sonic fan community. “Fan games,” have an uneven reputation. 2016’s AM2R was detail-obsessed to the point of alienating anyone not intimately familiar with Metroid 2 and Street Fighter x Mega Man (despite an official blessing from Capcom) missed the intangible je ne sais quoi from classic Mega Man. The proper balance between faithful appreciation and labyrinthine admiration is difficult to achieve. When it goes too far in either direction you usually wind up with, well, a fan game.

Enter the Sonic fan community. “Fan games,” have an uneven reputation. 2016’s AM2R was detail-obsessed to the point of alienating anyone not intimately familiar with Metroid 2 and Street Fighter x Mega Man (despite an official blessing from Capcom) missed the intangible je ne sais quoi from classic Mega Man. The proper balance between faithful appreciation and labyrinthine admiration is difficult to achieve. When it goes too far in either direction you usually wind up with, well, a fan game.

Sonic Mania escapes this stigma. Christian “Taxman” Whitehead, together with Headcannon (Simon “Stealth” Thomley), PagodaWest Games (Jared Kasl and Tom Fry)—all with either mobile game development experience and/or prominent names in the Sonic fan community—combined forces to build Sonic Mania with expertise, respect, and a sensible evaluation of Sonic’s strengths and weaknesses. They even contracted Tiago “Tess” Lopes, who’s long had a presence in the chiptune remix community, to retune original pieces and create brand new themes. Sonic Mania, while technically and faithfully produced by fans, was also a seasoned and shrewd collaboration between practiced veterans.

Problem #3 For the Love of Gimmicks

Problem #3 For the Love of Gimmicks

Part of Sonic’s character is wrapped in mechanics exclusive to individual levels. Casino Night Zone’s trademark pinball tables were as important to Sonic 2’s identity as the spinning, momentum-dependent top was to Sonic 3’s Marble Garden Zone. Gimmicks are a welcomed, though sometimes evasive, shift in performance and, in the case of Ice Cap Zone, a chance to infuse Sonic with modern extreme culture and allow him to snowboard down a mountain. The 90’s were a treasure.

Recent Sonic games have pushed gimmicks into absurdity. Sonic Unleashed felt the need turn Sonic into a wear-hog and turn half the game into a crude beat ’em up. Sonic Colors, with its context sensitive Wisps, was depending on what essentially amounted to magic to progress through a level. Sonic Generations, with its heart beating through classic levels, was at least smart enough to designate extraneous challenges as separate minigames.

In Sonic Mania, gimmicks rest comfortably outside the focus and not quite in the periphery. This objective is eased by the fact that eight of Sonic Mania’s twelve (and a half) zones return from previous Sonic games. While not an exact copy—Green Hill also incorporates the horizontal loop from Emerald Hill, for example—each returning zone’s first act is essentially a greatest-hits version of past zones. Flying Battery has its rocket slides and spinning poles, Hydrocity is loaded with water-skidding sequences, and Chemical Plant maintains its dreaded underwater shifting blocks.

Act 2 of each returning zone is usually where Sonic Mania plots its own course. Chemical Plant benefits from different colored pools of liquid that send Sonic sky high. Metallic Madness adapts Sonic CD’s sprite-scaling size disruption while shifting Sonic from the foreground to the background. Oil Ocean can combine Sonic 3’s fire shield with its pools of oil, effectively changing the flow and function of the entire zone. These instances aren’t just random ideas tossed in for the sake of novelty, but fully functional mechanics consistent with existing themes. They flow into (and out of) each level naturally, never sticking around too long.

Act 2 of each returning zone is usually where Sonic Mania plots its own course. Chemical Plant benefits from different colored pools of liquid that send Sonic sky high. Metallic Madness adapts Sonic CD’s sprite-scaling size disruption while shifting Sonic from the foreground to the background. Oil Ocean can combine Sonic 3’s fire shield with its pools of oil, effectively changing the flow and function of the entire zone. These instances aren’t just random ideas tossed in for the sake of novelty, but fully functional mechanics consistent with existing themes. They flow into (and out of) each level naturally, never sticking around too long.

As one might expect, Sonic Mania roars under the hood of its four original levels. The first act of Mirage Saloon (when playing as Sonic or Tails) is basically a horizontal shoot ‘em up with the trademark bi-plane the Tornado. The remainder compliments Act One’s western theme with ephemeral sarsaparilla pathways and disappearing, sandy speed loops. Studiopolis’ electric Hollywood theme features teleporting satellite vans, gravity loops, and silhouette tricks. Press Garden’s spin-friendly conveyer belts, tricky ice spikes, and Mega Man-inspired disappearing blocks feel like a frozen spin on Sonic 2’s Aquatic Ruin. Titanic Monarch, standing as Sonic Mania’s penultimate (but most challenging) zone, is rife with teleporting pink gas, momentum-demanding fling spheres, and what, in Act 2, essentially amounts to challenge rooms.

What’s not clear to the player is the exact reason for so many classic levels to appear inside Sonic Mania. Green Hill Zone is basically Sonic’s version of purgatory, a doomed cycle he’s had to repeat in Sonic Generations and (if you were extremely patient) Sonic Adventure 2. Chemical Plant, too, appeared in Sonic Generations. Sonic Mania’s four brand new zones and creative spins on existing zones prove the team knows how to make a great Sonic game. Sonic Mania was either a dry run for higher ambitions or a guiding line to ensure they stay on course. It’s difficult to marvel at the splendor of its original levels and not want a whole game composed of new stuff.

Sonic Mania’s lone game-wide contribution is the drop-dash. By holding down the jump button, Sonic can charge his spin dash in mid-air and deploy as soon as he makes contact with the ground. I found this useless and impractical, but I’m also not out there speed running through levels and making it seem essential. Others have also made a more reasonable case for the drop dash. It’s also worth mentioning that Sonic 3’s Insta-Shield and Sonic CD’s Super Peel Out can be unlocked, should you want something to replace the drop dash.

Problem #4 Reference, Reverence, and Relevance

Problem #4 Reference, Reverence, and Relevance

One of the benefits of fan games is the meticulous surge of obvious and oblique references. Translating minute obsessions to in-game references can be dangerous when infused to the point of alienating a casual (or ignorant) audience, but powerful when they’re able to slip by unnoticed. When you roll into the popcorn machine in Studiopolis you may think it’s a neat gimmick designed to toss Sonic around in the air. You may not know that it’s also a C-2 1993, SegaSonic Popcorn Shop, an AM1 popcorn/arcade machine exclusive to Japan.

The references don’t stop there. As detailed in Heidi Kemps’ feature over at GameSpot, Sonic Mania is full of them. References to Daytona USA’s artwork, Japan’s Club Sega arcades, Sega CD’s slogan, and Sonic & Knuckles’ lock-on technology are also present in Studiopolis. Unused goggles buried in the code of Sonic the Hedgehog are worn by Tails (or Sonic) when piloting the tornado biplane. Along the same lines, Splats (an unused rabbit Badnik from Sonic 1) appears in two zones and giant checkered-board ball, seen in pre-release coverage of the original game, can be accessed through Sonic Mania’s debug mode and dropped into Green Hill Zone.

Studiopolis is the clear home to most of Sonic Mania’s references, but Mirage Saloon pulls off a fair amount too. Its foundation is rooted in Sonic 2’s fabled Dust Hill Zone, a desert themed zone cut from Sonic 2. Previously seen only in mock up shots sent to magazines, we knew it had cactuses, canyons, and sand and—unlike Hidden Palace Zone—it didn’t resurface in Sonic 3 & Knuckles’ Sandopolis. Taxman nearly included Dust Hill Zone, remixed as Desert Dazzle Zone, in his 2011 remastered of Sonic CD (a welcomed change he did accomplish with the original Hidden Palace Zone in Sonic 2’s iOS ports).

Mirage Saloon’s callbacks don’t end with implicit citations to deleted content. Act 2’s trio of bosses are all infamous samples from Sega’s abominable menagerie. Bean the Dynamite, inspired by Bin and Pin from AM2’s Dynamite Dux, was first (and last) seen in Sonic the Fighters and, locally the Saturn’s Fighters Megamix. Bark the Polar Bear followed the same path, minus an inauspicious arcade origin. Fang the Sniper, known stateside as Nack the Weasel, debuted in Game Gear’s Sonic Triple Trouble, and also made an appearances in Sonic the Fighters can the infamously canceled Sonic X-treme.

As the most powerful surprise of Sonic Mania, Dr. Robotnik’s Mean Bean Machine concludes the second act of Chemical Plant Zone. A sample from the 1994 North American Genesis exclusive, which is really just a Sonic’d up version of Puyo Puyo, was the last thing anyone expected to find as a boss fight in Sonic Mania. It isn’t especially hard to beat Robotnik, a combination of luck and intuition goes pretty far in Puyo Puyo, but its basic inclusion is one of Sonic Mania’s deepest cuts. Thanks to some clever details in Act 2, there’s also a contextually appropriate reason for its inclusion.

Problem #5 Sonic’s Specialty

Problem #5 Sonic’s Specialty

Sonic’s special stages are technical marvels that range from to passably functional to mildly irritating. Sonic 1’s falling-ball pinball maze thing was neat but disorienting. Sonic 2’s prerendered sprites running through a pseudo-3D half pipe was the most amazing thing I had ever seen when I was 7 years old, but imprecise and aggravating (and watching Tails suicide run into bombs didn’t help). Sonic 3 & Knuckle’s sphere-maze-puzzle, Blue Sphere, was frustrating but dependable. Sonic CD’s sprite scaling and rotation was technically impressive but it was tough to get a grip on perspective when chasing down a myriad UFO’s.

Sonic Mania’s bonus stages, accessible by hitting a starpost checkpoint with at least 25 rings, reprise Sonic 3 & Knuckles’ Blue Sphere minigame with brand new stages. Thirty-two are available and neatly reprise Sonic 3’s call for reaction, efficiency, and planning. It’s clear why people hate Blue Sphere, perspective tricks that were impressive in 1994 may seem chaotic and obscured today, but it’s so much fun once you get the hang of it. Finishing a stage rewards the player with a silver medal while completing it, which entails getting all rings (and potential spheres turned into rings) before grabbing the last remaining sphere, awards a gold medal. While the latter treats the player with a suite of neat easter eggs and unlockable options, I achieved gold on every stage for the sheer joy of completion. It was hard, but I always came just close enough to make them feel attainable.

For Sonic Mania’s special stage, I’d like to think the development team looked to Sonic Team’s condensed work on Sonic 3D Blast. While Traveler’s Tales handled development of the core Genesis game and Saturn port, Sonic Team created polygonal special stages exclusively for the Saturn release. These largely followed the half-pipe model established in Sonic 2, but a basic polygonal assembly and true-3d orientation was the first time we had ever seen Sonic as a functional part of the next generation (The bonus level in the Saturn’s Sonic Jam compilation furthered this dream, of course, but that was more of a working prototype for what eventually turned into Sonic Adventure).

For Sonic Mania’s special stage, I’d like to think the development team looked to Sonic Team’s condensed work on Sonic 3D Blast. While Traveler’s Tales handled development of the core Genesis game and Saturn port, Sonic Team created polygonal special stages exclusively for the Saturn release. These largely followed the half-pipe model established in Sonic 2, but a basic polygonal assembly and true-3d orientation was the first time we had ever seen Sonic as a functional part of the next generation (The bonus level in the Saturn’s Sonic Jam compilation furthered this dream, of course, but that was more of a working prototype for what eventually turned into Sonic Adventure).

Sonic Mania’s special stage reprises the UFO-hunt objective from Sonic CD, but condenses it to a single UFO across a flat, maze-like plane. Sonic (or Tails or Knuckles) is assembled with few but effective 3D polygons, adding fuel to Sonic Mania’s 32-bit what-if fire. Sonic can collect hordes of respawning blue spheres to level up his speed and pockets of finite rings to extend his time. The UFO initially travels faster than Sonic, but, once Sonic hits mach 3, it’s simply a matter of navigating the course, keeping up with rings, and trying not to fall off the stage or run into bumpers. It’s as if Sonic R didn’t have to be a traditional racing game, but rather an objective-focused sprint toward a shifting goal.

The development team couldn’t have found a smarter way to pay homage to Sonic’s past, obey their own pseudo 32-bit generation guidelines, and make a minigame that’s, well, actually playable from a modern perspective. Sonic Mania’s UFO stages require a certain degree (and, across seven stages, gradual refinement of) skill; it is hard, but it’s not sloppy or experimental like a lot of early attempts from the PlayStation, Saturn, and 3DO. Completing all seven stages for each character nabs all seven chaos emeralds, enabling both Super Sonic and access to the hidden final zone, Egg Reverie. These incentives are consistent with Sonic 3 & Knuckles’ model, only this time the stages’ novelty and performance feel rewarding enough on their own merits.

Problem #6 Gotta Go Fast

Problem #6 Gotta Go Fast

The meme is the reality. Sonic has to go fast. It is his blessing and it is his curse. The ability that defines his character is also the catalyst that drives him wildly out of control. The solution for this, at least in his 3D outings, is to closely monitor his path. Sonic Adventure, with Emerald Coast’s whale chase sequence, was famous for locking Sonic to a short-term track. Rail grinding, now a staple of Ratchet & Clank, was another solution Sonic Adventure 2 and Sonic Heroes frequently embraced. Sonic 2006 and Sonic Generations’ 3D segments rested on the same principles. It was exhilarating when it worked, but it only worked like half the time. Either Sonic broke or (especially in the case of Sonic 2006) the game literally broke, wiping out any chance of appreciating Sonic’s explicit speed.

Sonic Mania offers two primary solutions for developing a sense of momentum. The first, through a combination of bumpers, loops, and other instant-speed devices, inserts Sonic in a carefully controlled Rube Goldberg machine. Through Sonic Mania’s physics engine, Sonic is easily allowed to drift and fall into highly specific segments that, in a first impression, appear to be pure chaos. These sequences are undoubtedly the result of tireless trial-and-error testing, widening gaps and increasing the potency of bumpers until Sonic fell just right into the proverbial go-fast machine.

The other solution is the primary stereotype of Sonic games. The player holds forward and Sonic just runs. It’s mindless, skill isn’t exactly being tested here, but it’s visually rewarding at the same time. Stardust Speedway proves to be the ultimate example of both, discarding the other level’s tiered pathways in favor of more open, accessible speed tracks (leaving little doubt why Stardust Speedway was chosen for the “beat an act in under one minute” trophy). In practice Sonic isn’t actually about speed, the bulk of the original 16-bit games were actually focused on traditional platforming, but Sonic Mania needed to exhibit tangible, constant speed in order qualify as a modern Sonic title (interestingly, Sonic can actually get too much speed and begin to veer out of the center of the screen, an effect deliberately carried over from older games).

One zone, in particular, comes up with a new way to keep Sonic moving forward. Act 2 of Oil Ocean slowly fills the screen with opaque gas, obscuring the player’s point of view and, eventually melting away rings until Sonic dies (this also neatly aligns with Sega’s 90’s environmentalism, detailed in Jason Koebler’s article at Motherboard). Scattered throughout the stage are giant levers Sonic can pull to clear the screen and reset the onslaught of toxic fumes. This isn’t particularly hard, levers are plentiful and Sonic is practically thrown at them, but it remains an effective means of propelling Sonic forward.

One zone, in particular, comes up with a new way to keep Sonic moving forward. Act 2 of Oil Ocean slowly fills the screen with opaque gas, obscuring the player’s point of view and, eventually melting away rings until Sonic dies (this also neatly aligns with Sega’s 90’s environmentalism, detailed in Jason Koebler’s article at Motherboard). Scattered throughout the stage are giant levers Sonic can pull to clear the screen and reset the onslaught of toxic fumes. This isn’t particularly hard, levers are plentiful and Sonic is practically thrown at them, but it remains an effective means of propelling Sonic forward.

For the first time I can personally remember, the clock is a factor in Sonic Mania. There were three or four instances where, in the middle of boss fight, I would die for absolutely no reason. What I assumed was a glitch was revealed to be the clock striking ten minutes. This is actually plenty of time to get through a level, Sonic’s speed allows him to churn through the landscape, but the experimentation and demands made by Sonic Mania’s bosses might eclipse the clock on an initial run through the game.

It’s unclear whether the clock is a viable paean to Sonic’s obsession with speed. Sonic Mania’s levels are huge, most with at least three different paths through a single act. There isn’t a lot of room for backtracking, Sonic basically burns down a level’s architecture as he moves through it, but it actively discourages exploration. To find a new path the level must be played over again, which is a perspective that only exists in a world where people play games multiple times. Sonic Mania doesn’t appear to care that most of the world has moved on from that point of view, which, again, neatly aligns its motives with its 32-bit aspirations. It’s hard to fault this perspective.

Problem #7 Opposition

Problem #7 Opposition

If Sonic has to go fast then surely his enemy is anything that slows him down. It would be difficult to accomplish this purely through level design. How do you simultaneously encourage and discourage speed? The natural solution is to make the obstacles sentient, and place Badniks in specific positions across every level. The result is Sonic barreling head first into robotic annoyances, scattering rings in every direction and frustrating the ever loving shit out of players. It doesn’t especially matter, rings are plentiful and hundreds can be acquired in every level, but it successfully halts momentum. Sonic has to face his enemy.

Perhaps this is best illustrated through the Turbo Spiker. It’s a crab looking Badnik that fires off a giant spike rocket when Sonic approaches. Jumping over it results in Sonic getting demolished by the rocket while running into it head-on also impales Sonic on the rocket. What you’re supposed to do is tuck Sonic into a ball whenever he starts going really fast, a lesson both Sonic 3 (where the Turbo Spiker debuted in Hydrocity) and Sonic Mania (still in Hydrocity!) hope the player would have learned before the introduction of the Turbo Spiker. Tough love is then employed, basically forcing the player to incorporate the tuck if they would prefer to see a different result.

Sonic Mania’s original Badniks do well to work inside of Sonic’s (along with Knuckles and Tails’) limited mechanics. Studiopolis’ Tubinauts have three non-threatening shields that impede progress and, essentially, create an enemy that demands four consecutive attacks. The Shutterbug isn’t too dissimilar from a basic flying enemy, it just slows down, disrupting basic expectations, in order to take a picture of Sonic. Juggle Saws, two opposing spiders that pass a buzz saw back-and-forth in Press Garden, present a rare tandem Badnik, requiring the player to properly time which one to attack first.

Sonic Mania’s original Badniks do well to work inside of Sonic’s (along with Knuckles and Tails’) limited mechanics. Studiopolis’ Tubinauts have three non-threatening shields that impede progress and, essentially, create an enemy that demands four consecutive attacks. The Shutterbug isn’t too dissimilar from a basic flying enemy, it just slows down, disrupting basic expectations, in order to take a picture of Sonic. Juggle Saws, two opposing spiders that pass a buzz saw back-and-forth in Press Garden, present a rare tandem Badnik, requiring the player to properly time which one to attack first.

Sonic’s ability, or lack thereof, to engage and dismiss enemies has always presented a difficult problem. Sonic Mania addresses this issue, but it doesn’t completely solve it. There still aren’t firmly established ground rules (why does Sonic bounce off some enemies he vanquishes and move right through others?) and a lot of Badniks feel like they’re only out there to take up space. Sonic is bound to basic rules established a quarter century ago. Veering too far away makes it not Sonic and modifying them too heavily disrupts basic action. Sonic 3’s split-second insta-shield and three different elemental shield options are the hardest it’s ever been pushed (and Sonic Mania makes great use of all three), but it’s an imperfect solution. Levels are only populated with enemies because, presumably, something needs to try and slow Sonic down.

Problem #8 Organic Mechanics vs Synthetic Routine

Problem #8 Organic Mechanics vs Synthetic Routine

Boss battles present an entirely different set of problems for Sonic to overcome. And like the elements of Sonic Mania’s level design, they’re not only facing off against 2017, but also five different Sonic games. In some instances, such as Green Hill Zone’s Death Egg Robot and the Metal Sonic battle in Stardust Speedway, Sonic Mania remixes and resets previous Sonic boss fights. A majority of them, however, press Sonic’s meager move set against a surprising variety of applications.

Sonic Mania’s best boss battles are against its quintet of Hard Boiled Heavies. The fight against Heavy Gunner takes a page from Sonic CD’s racetrack fight against Metal Sonic and creates make-shift hurdles out of different colored missiles. Heavy Rider’s fight, at the end of Mirage Saloon, embraces Sonic’s goofy proclivity for insane sideshows. He rides a roller coaster in and out of the background, taking swipes at Sonic under the stress of shifts in perspective. Heavy Magician, mentioned earlier, conjures the specters Nack, Bean, and Bark for three diverse fights in one. Heavy Shinobi’s fight, which relies on knocking him out of his jump attacks, is more pedestrian, but at least Sonic finally gets to fight a guy with a sword.

Bosses outside of the Hard Boiled Heavies have a lower threshold for theatrics but aren’t left wanting for creativity. Robotnik’s Weather Globe, concluding Studiopolis, uses three different weather patterns to shift Sonic into different safe zones around the screen. Big Squeeze is essentially a garbage compactor, compressing the screen full of busted Badniks until Sonic is able to jump high enough to cause some damage. The DD Wrecker, two wrecking balls with a chain between them, is as close as Sonic Mania gets to a traditional boss fight, and is well placed at the end of the very first level.

Bosses outside of the Hard Boiled Heavies have a lower threshold for theatrics but aren’t left wanting for creativity. Robotnik’s Weather Globe, concluding Studiopolis, uses three different weather patterns to shift Sonic into different safe zones around the screen. Big Squeeze is essentially a garbage compactor, compressing the screen full of busted Badniks until Sonic is able to jump high enough to cause some damage. The DD Wrecker, two wrecking balls with a chain between them, is as close as Sonic Mania gets to a traditional boss fight, and is well placed at the end of the very first level.

Sometimes Sonic Mania tries to push Sonic too hard, considerably opening up its own margins of error. The Spider Mobile, which concludes Flying Battery, constantly elevates the floor and demands Sonic grab onto intermittent spinning columns. Swinging off those into the Spider Mobile, pushing it into a row of spikes, is more depending on luck than an application of skill or timing. Giga Octus, the tentacled foe concluding Act 2 of Oil Ocean, straight up sucks. The holy trinity of Sonic Sins—removing the recovery of rings, unpredictable elements of surprise, and drowning—are employed simultaneously, creating a fight that’s more about endurance and survival than read and reaction.

Sonic Mania seems to have too much on its plate. The challenge of having thirteen levels, all but one with two acts each (along with an act and boss of Mirage Saloon specifically for Knuckles), may have spread Sonic Mania’s trio of developers too thin. This is a relatively common problem—it’s a struggle to think of any game, even from the Souls series, without a dud or two among its boss lineup—but you always hope for the best in a revival with the strength and goodwill of the remainder of Sonic Mania.

Problem #9 Opaque Direction & Seething Frustration

Problem #9 Opaque Direction & Seething Frustration

This is a problem Sonic Mania doesn’t solve. There are a considerable number of instances where level design choices and basic mechanics break down and unjustly destroy the player. Like the enigmatic barrels of Sonic 3’s Carnival Night Zone, certain aspects of Sonic Mania that may have seemed clear to the development team (and/or focus groups) wind up bewildering and frustrating a larger audience.

One problem, in particular, persists throughout the entire series. If Sonic is running toward an object, and that object is moving against a wall, Sonic will die instantly if he falls inside the closing gap. This somehow happens all the time, often by no fault of the player. Worse, Sonic doesn’t lose his rings with any chance of recovery, he just dies and you’re sent back to the last checkpoint. God be with you if that was your last life and you end up repeating the entire level.

Other instances appear to be tied to Sonic Mania’s basic operation. The first phase of Laundro Mobile, the boss of Hydrocity act 2, positions Sonic underwater and demands the use of intermittent air bubbles. The problem is sometimes, but pure random chance, these bubbles simply don’t appear, effectively rendering any chance at victory impossible. More modern problems are also common; falling through the floor, hard crashes back to the PlayStation 4’s operating system, and repeatable collision issues seem to be part of gaming life in 2017.

Sonic Mania also contains a few segments that seem tuned frustrate the player. Chemical Plant Zone’s underwater shifting blocks, pulled straight from Sonic 2, still smash and destroy Sonic with indifferent malice. Joining them are Titanic Monarch’s parallel elevator columns, demanding Sonic move on and off them at the exact right moment if he doesn’t want to be crushed to death. Hearing the badumm death rattle and watching Sonic fly helplessly down the screen is crushing.

Games are supposed to be challenging, especially when they’re modeled as a retro experience. Sonic ironically wouldn’t be Sonic if it weren’t occasionally dragged down by puzzling design choices and sporadic instances of unsportsmanlike conduct. That being said, Sonic Mania feels bound to a thesis containing little other than zeal and exuberance, and seeing it crash head first into one of these walls can only feel disappointing.

Problem #10 Being This Good Takes Ages

Problem #10 Being This Good Takes Ages

While not exact, the saga of Star Wars presents close parallels to Sonic’s cycle. After the prequels wrecked shop and shat upon a civilization’s greatest space opera, The Force Awakes debuted in 2015 and corrected a perilous course. It wasn’t everything Star Wars could be, in fact much of its plot beats and characters deliberately repeated its past, but it got the franchise back on track. Mostly Better Than Average felt good because Star Wars had been bad since 1999.

Hubris is an unfortunate but sometimes necessary catalyst to moving forward. Had Sega not hilariously mismanaged Sonic 4 or thought to develop proper sequels to Sonic Lost World, Sonic Generations, or Sonic Unleashed, there may have been no impetus to hand Sonic Mania over to a fresh trio of outside developers. Taxman’s work on Sonic CD and the Sonic 2 mobile ports (along with M2’s work on Sonic 1 and Sonic 2’s glorious 3DS revivals) must have spoken louder than failed console initiatives, waking up someone over at Sega big enough to call the shots.

After Sonic the Hedgehog (2006) bottomed out at the beginning of the last generation, Sonic’s been trying to get enough speed to circle out of the bottom of the barrel. Sonic Mania, at long last, eclipsed the top, freed Sonic, and rid Sega of a millennial curse. Sonic Forces hopes to continue this trend. If it doesn’t—and gosh it doesn’t look like it will— it’s hard to see Sonic Mania’s attention not demanding a sequel of its own.

It’s easy to love Sonic Mania. This is impressive when you remember the core of Sonic Mania’s audience found it tough to even like Sonic for any time after 1994.

Problem #1 2D or not 2D

Problem #1 2D or not 2D Problem #2 Sonic Team

Problem #2 Sonic Team  Problem #3 For the Love of Gimmicks

Problem #3 For the Love of Gimmicks Problem #4 Reference, Reverence, and Relevance

Problem #4 Reference, Reverence, and Relevance Problem #5 Sonic’s Specialty

Problem #5 Sonic’s Specialty Problem #6 Gotta Go Fast

Problem #6 Gotta Go Fast Problem #7 Opposition

Problem #7 Opposition Problem #8 Organic Mechanics vs Synthetic Routine

Problem #8 Organic Mechanics vs Synthetic Routine Problem #9 Opaque Direction & Seething Frustration

Problem #9 Opaque Direction & Seething Frustration Problem #10 Being This Good Takes Ages

Problem #10 Being This Good Takes Ages